Hi. Today, it's Sunday morning. I'm doing some research. I was just a little curious about whether anybody else had explored this aspect of the Flitcraft Parable. The Flitcraft Parable, if you're not familiar with it, is a small digression in the story, The Maltese Falcon. It has nothing to do with the mystery. It is a complete digression and I'm looking at various interpretations of it. And nobody talks much about Mrs. Flitcraft. That's what's always kind of gotten me. You have to realize that this is a story told by Sam Spade to Brigid O’Shaughnessy, his client, for some reason or other.

But the thing is, you are getting Sam Spade's version of what Mrs. Flitcraft told him. I'll just read it to you:

Spade sat down in the armchair beside the table and without any preliminary, without an introductory remark of any sort, began to tell the girl about a thing that had happened some years before in the Northwest. He talked in a steady matter-of-fact voice that was devoid of emphasis or pauses, though now and then he repeated a sentence slightly rearranged, as if it were important that each detail be related exactly as it had happened.

At the beginning Brigid O'Shaughnessy listened with only partial attentiveness, obviously more surprised by his telling the story than interested in it, her curiousity more engaged with his purpose in telling the story than with the story he told; but presently, as the story went on, it caught her more and more fully and she became still and receptive.

A man named Flitcraft had left his real-estate-office, in Tacoma, to go to luncheon one day and had never returned. He did not keep an engagement to play golf after four that afternoon, though he had taken the initiative in making the engagement less than half and hour before he went out to luncheon. [This has not been spelled checked, obviously.] His wife and children never saw him again. His wife and he were supposed to be on the best of terms. He had two children, boys, one five and the other three. He owned his house in a Tacoma suburb, a new Packard, and the rest of the appurtenances of successful American living.

Flitcraft had inherited seventy thousand dollars from his father, and, with his success in real estate, was worth something in the neighbourhood of two hundred thousand dollars at the time he vanished. His affars were in order, though there were enough loose ends to indicate that he had not been setting them in order preparatory to vanishing. A deal that would have brought him an attractive profit, for instance, was to have been concluded the day after the one on which he diappeared. There was nothing to suggest that he had more than fifty or sixty dollars in his immediate possession at the time of his going. His habits for months past could be accounted for too thoughly to justify any suspicion of secret vices, or even of another woman in his life, though either was barely possible.

"He went like that," Spade said, "like a fist when you open your hand,"

...

"... Well, that was in 1922. [depending on what edition of this book you read, incidentally] In 1927, I was with one of the big detective agencies in Seattle. Mrs. Flitcraft came in and told us somebody had seen a man in Spokane who looked a lot like her husband. I went over there. It was Flitcraft, all right. He had been living in Spokane for a couple of years as Charles - that was his first name - Pierce. He had a automobile-business that was netting him twenty or twenty-five thousand a year, a wife, a baby son, owned his home in a Spokane suburb, and usually got away to play golf after four in the afternoon during the season."

Spade had not been told very definitely what to do when he found Flitcraft. They talked in Spade's room at the Davenport. Flitcraft had no feeling of guilt. He had left his first family well provided for, and what he had done seemed to him perfectly reasonable. The only thing that bothered him was a doubt that he could make that reasonableness clear to Spade. He had never told anybody his story before, and thus had not had to attempt to make its reasonableness explicit. He tried now.

"I got it all right," Spade told Brigid O'Shaughnessy, "but Mrs. Flitcraft never did. She thought it was silly. Maybe it was. [Silly, huh?] Anyway it came out all right. She didn't want any scandal, and, after the trick he had played on her - the way she looked at it - she didn't want him. So they were divorced on the quiet and everything was swell all around.

"Here's what happened to him. Going to lunch he passed an office-building that was being put up - just the skeleton. A beam or something fell eight or ten stories down and smacked the sidewalk alongside him. It brushed pretty close to him, but didn't touch him, though a piece of the sidewalk was chipped off and flew up and hit his cheek. It only took a piece of skin off, but he still had the scar when I saw him. He rubbed it with his finger - well, affectionately - when he told me about it. He was scared stiff of course, he said, but he was more shocked than really frightened. He felt like somebody had taken the lid off life and let him look at the works."

This is the part everybody always focuses on. The lid came off of life and he had to look at the works. Oh!

“Flitcraft had been a good citizen and a good husband and father, not by any outer compulsion, but simply because he was a man most comfortable in step with his surroundings". [Interesting. Most in step with his surroundings.] "and a good citizen and a good husband.”

People can seem good on the outside and be really shitty on the inside. Have you ever noticed that? Oh, anyway.

"He had been raised that way. The people he knew were like that. The life he knew was a clean orderly sane responsible affair. Now, a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things. He, the good citizen-husband-father [allegedly], could be wiped out between office and restaurant by the accident of a falling beam. He knew then that men died at haphazard like that, and lived only while blind chance spared them.” [Gee, really? Tell me something. I don't know.]

“It was not, primarily, the injustice of it that disturbed him: he accepted that after the first shock. What disturbed him was the discovery that in sensibly ordering his affairs he had got out of step, and not in step, with life. He said he knew before he had gone twenty feet from the fallen beam that he would never know peace until he had adjusted himself to this new glimpse of life. By the time he had eaten his luncheon he had found his means of adjustment. Life could be ended for him at random by a falling beam: he would change his life at random by simply going away. He loved his family, he said, as much as he supposed was usual [whatever that means], but he knew he was leaving them adequately provided for, and his love for them was not of the sort that would make absence painful.”

[His love was not of the sort that would make absence painful? Wow. That tells you something. I think.]

“He went to Seattle that afternoon," Spade said, "and from there by boat to San Francisco. For a couple of years he wandered around and then drifted back to the Northwest, and settled in Spokane and got married. His second wife didn't look like the first, but they were more alike than they were different. You know, the kind of women that play fair games of golf and bridge and like new salad-recipes. He wasn't sorry for what he had done. It seemed reasonable enough to him. I don't think he even knew he had settled back naturally in the same groove he had jumped out of in Tacoma. But that’s the part of it I always liked. He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.

See, that's the part I always love. He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell and he adjusted himself to them not falling. This is taken from Dashiell Hammett's, The Maltese Falcon, chapter seven, entitled “G in the Air,” pages 61-64, according to this thing I'm reading, which is not very well, was not spellchecked or checked for grammar or anything. Well-checked for whatever. [I could have sworn I’d cut that part out. Oh, well.] It occurred to me that Spade only knows this based on what he heard from Mr. Flitcraft, and he only gets involved in the case because Mrs. Flitcraft came to him to verify a rumor that her husband was alive.

I don't think he did a real thorough check on Mrs. Flitcraft. He seems to know a lot about Mr. Flitcraft. He seems to know a lot about Mr. Flitcraft, but tells you virtually nothing about Mrs. Flitcraft. Okay? Having said that, I have now created a whole backstory for Mrs. Flitcraft, and let me tell you something. She didn't have any kids. She was lying about that, in my backstory. She was lying about a lot of things to Spade, and Spade was not getting it. Talk about having the lid taken off your life. Yeah. Mrs. Flitcraft was questioning a whole lot of normal when you come right down to it, in my version of her world, and it is not, in answer to somebody's question, a violation of a copyright for me to invent a backstory about a character in this novel that the author himself never thought to create [one for] because she was just like the second wife, one of those women who play a fair game of golf and bridge and like new salad recipes. That wasn't Mrs. Flitcraft at all. So there you go.

That's part of the process of writing about this character who nobody ever wrote about before and never assume. Boy, never assume that people are always telling you the truth. Sam Spade. (Ha!) I had the lid ripped off my life. I had a stroke at the age of 48, and then I got dystonia. How about them apples?

Here’s some of the research that turned up about the Flitcraft Parable.

Will White People Forget About George Floyd? (A parable embedded in The Maltese Falcon offers a cautionary tale.)

Twenty Writers: Dashiell Hammett, The Flitcraft Parable (from The Maltese Falcon).

BONUS LINKS:

Massive prehistoric solar storm is warning for Earth, researchers say.

A new U-Md. research center will study fairer, greener transportation networks.

Career Coach: Why you should slow down and enjoy your coffee.

Deciphering the ABCs of Medicare open enrollment.

Ha! You ain’t kidding. :)

Opinion: The word ‘But’ asks that it not appear in these sentences.

RIP Suzanne Somers. “She became famous for playing, as she put it, ‘one of the best dumb blondes that’s ever been done,’ then became a sex-positive health and diet mogul.”

So, anyhow …

You have the right to remain silent, but what fun is that? :)

Uh huh … life can get really complicated.

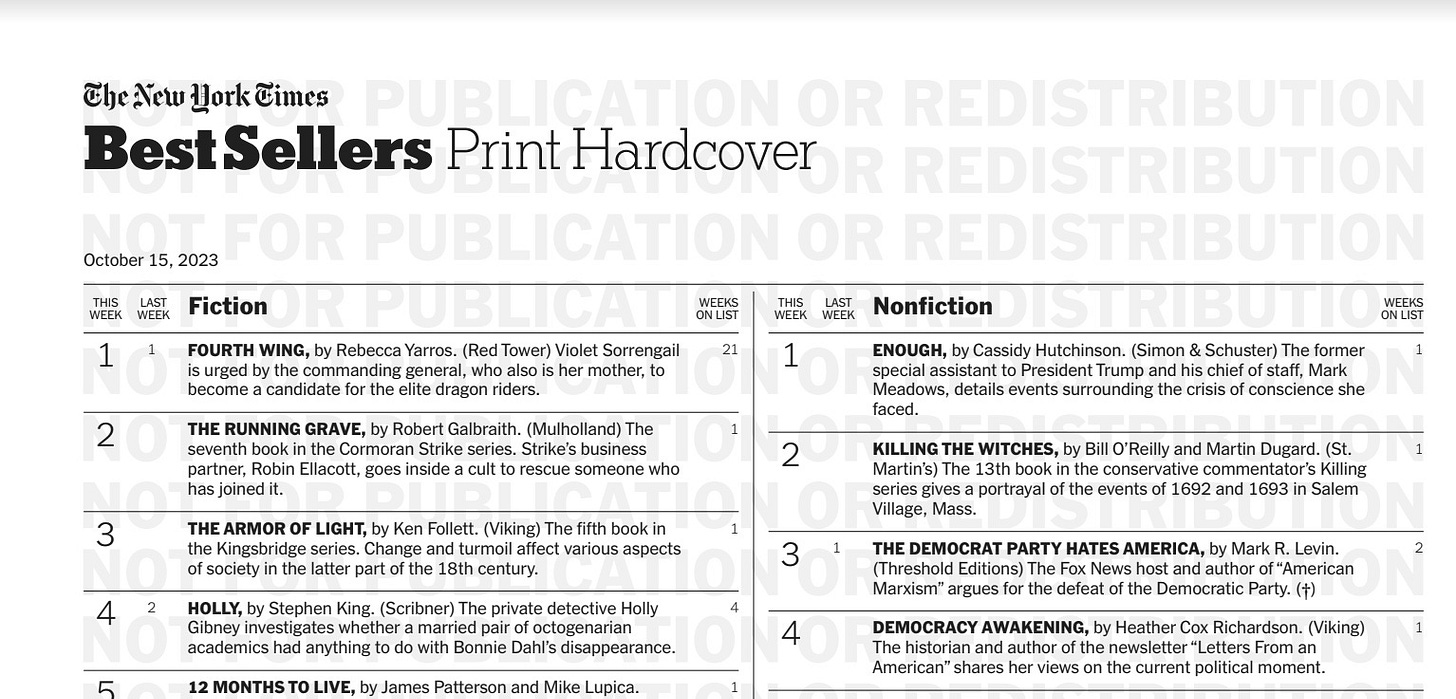

Look who made the bestseller list! Wow! People do still buy/read print books!

PPS: The World is Too Much (a poem) (with analysis).

PPPS: Here’s my short film about Mrs. Flitcraft!

Share this post